The dynamics of teaching, learning, researching parenting and regulating – an ecosystem where we all play a role

Students, teachers, academics, parents and institutions all play a part in the education system. Do we need to appreciate each other a little more?

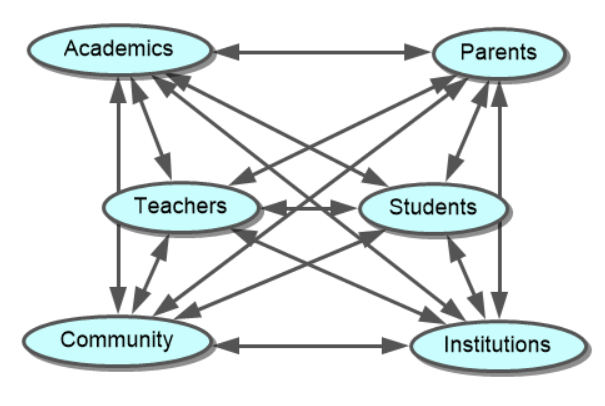

Below I tried to represent in simple fashion the very complex education system. I haven’t included commercial organisations that provide particular products for classrooms, which play an important role in our education system. My aim in showing this is to highlight the need to communicate efficiently with other elements of the system. You’ll notice that in the center of the system, I put the students and teachers, with the other elements on the periphery. This is because I think of the teacher-student relationship as the most important one when looking at a system that rests on the learning-teaching dyad.

To illustrate my point, at the second of our bi-yearly ‘student-led interviews’ this year, a parent told me that their daughter was a visual learner and that I should provide her with more visual material. This was not the first time, nor it will be the last time, that I heard this. I am also quite convinced that many teachers will have experienced this. Unlike previous occurrences when I have brushed it off, I gave this one some thinking.

As far as I was concerned, although there was no tension between the parent and me, this meeting was an unmitigated failure – and it was not just because the parent was pushing the learning style thing. It was because despite sharing a common goal, we could not come to an agreement on how to best guide the student in her education. The parent was armed with an explanation for their daughter’s difficulties in my class, I was feeling annoyed for being told how to do my job and to have the learning styles theory pushed on to me, the daughter was sitting there, impassive, all three of us locked in this mandated 5-minute meeting, inadequate to provide anything constructive to this family. Why meet if there is no intention to communicate?

Ok, so I’ve chosen a situation where communication failed in order to illustrate how different elements fit in the education system. I could have chosen any number of the many very positive interactions I have had. It’s just that the above situation stayed with me, and led to me to think more deeply about what had gone wrong.

So this event was the catalyst to thinking about my position within the system.

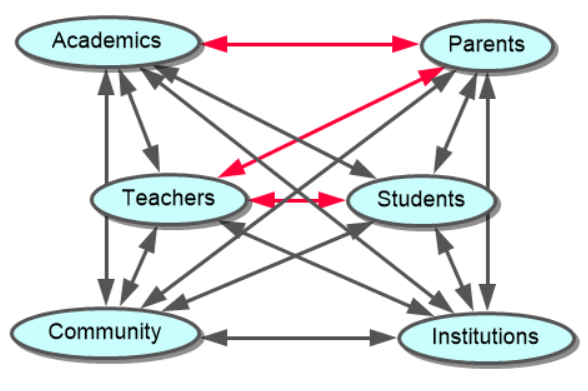

If you imagine that event through the web of relationships possible as showing in the graphic above, you can identify where there might be a tension. In red, in the figure below, I maked which elements were not communicating efficiently, leading to the failure of our meeting.

From my perspective, it appeared that the parent and child had broken possible communication by imposing their viewpoint and by drawing on a dubious educational theory without giving me a chance to respond. An interesting consideration is to contrast the ‘negative’ relationships with the positive ones, as they allow to group particular elements. From my teacher perspective, then, I saw a family distancing itself from the professional educational dimension of the system, emphasising the parent-daughter relationship.

With this emphasis, my first organisation of the web of relationship is challenged, replacing the teacher-student as the nucleus with parent-teacher dyad. There was power at play. What if, then, the parent-child dyad was central to her education, the teacher in periphery. It is not a crazy idea – there are a number of studies showing that teachers have a very small impact on a student’s learning and that the student’s background is much more important.

This could be a more exact representation. I’d like to think that the direct action of teaching in a classroom has more impact, but I am ready to question it. What is more relevant, in my opinion, whether you accept teacher-student or parent-child dyad as central to a child’s education, it remains in the realm of our professional responsibility to facilitate communication between the different parties.

Something I failed to do on that night was to try to put myself in the parent’s shoes. Had I tried, maybe I would have understood better how to address the situation. In any case, I can’t assume that all parents will see me as the person central to their child’s education. After 6 years of primary school which a new teacher each year, and all specialist teachers in high school, my position in the overall scheme of things might seem pretty incidental. I might have to acknowledge that the people this student will see every single day isn’t me or my colleague, but her family.

While my impact on a single student’s overall learning trajectory is minimal if time spent teaching them alone is considered, it is what I do with that time that matters. The way I build relationship with the student, teach the content, allow them to express themselves, to contribute, to feel valued, the way I grab their attention, feed their imagination, pass on my passion, show kindness, patience, uphold good behaviour and respectful etc, all that improves the quality of that bond within the system.

This is why when I see lists of pedagogical strategies designed to improve the learning of my students, I know that their success in my classroom depends very much on the relationship I have with them individually and as a group, and their relationships independent of me.

In the next few blogs, I’d like to explore some of the bonds inherent to the system as I see it. I’d like to explore some of the characteristics that define those specific bonds, discuss where pitfalls might exist, and even how to tackle them. It’s not a finger pointing exercise, but rather a call for more effective and respectful conversation, discussion or debate, whatever you want to call it. I believe that by improving the dynamics between the different elements of the system, we may improve our education system as a whole.